It’s been a while since I blogged about topical research, so it’s time to dust off this particular thinkin’ cap and give it a whirl. This post is about three recent projects I’ve been involved in that (I think) are currently all in press or just-published, even though one of them started in 2013, one in 2015, and one just last year. No, I ain’t terribly fast at this publishing game. And yes, I am watching a favorite Western movie as I type, Friendo, so pardon the drawl.

Enough perambulatin', on to the post!

It starts with a simple question: How many atheists are there?

If, like me, you study religious cognition, this is a hugely important question. Theories may live or die based on the answer to it.

Easy enough to answer…just ask people. Pollsters have been doing this in the US for decades. And the answer you get depends on the question you ask.

3% of Americans. Or maybe that's 11%. Hmmm....

If you give people a menu of religious identifications (Catholic, Lutheran, Hindu, Sikh, Sunni, Atheist, Agnostic, …), it turns out around 3% Americans identify as atheists. Problem solved, it’s 3% let’s go have a beer to celebrate.

Not so fast…what about people who don’t believe in any gods, but who for whatever reason did not check the “atheist” box on the menu? They might do this for lots of reasons (including terminological confusion). So let’s take a definitional approach: ask people whether or not they believe in any gods. If they say no, BAM, atheist. Now you’re looking at around 11% of Americans. Not so hard, and that beer is probably still cold.

Long story short, Maxine Najle and I suspected that this 11% figure was probably too low (published at SPPS). Maybe even way too low. Simply because that figure comes from telephone polls, where people have to tell a stranger they don’t believe in God. And lots of people might not want to do that. Whence this reluctance? That leads to the other two projects.

It turns out that atheists aren’t all that especially popular in large parts of the world. Just how unpopular, you ask?

Hero squad

This next project involved an uber team of 13 authors. Much thanks to them. We decided to run the same exact experiment in 13 countries to check out people’s intuitive moral distrust of atheists. It's now out at Nature Human Behavior.

To do this, we turned to a classic task by Tversky and Kahneman on the conjunction fallacy:

Linda is 31 years old, single, outspoken, and very bright. She majored in philosophy. As a student, she was deeply concerned with issues of discrimination and social justice, and also participated in anti-nuclear demonstrations.

Which is more probable?

Linda is a bank teller.

Linda is a bank teller and is active in the feminist movement.

Most people pick the latter option, even though it logically can’t be true (hint: all feminist bank tellers are also bank tellers). They do this because they’re using the representativeness heuristic, which is a fancy way of saying that intuitively the description of Linda just sounds like someone active in the feminist movement.

You can have all sorts of fun with this task by tinkering with the description given of Linda, and by plugging in different potential groups in the second option. People only tend to pick the second option when the group in it intuitively matches the description provided.

In our study, we gave people a description of a creepy serial killer who mutilates homeless people for fun. Then we asked whether it is more probable that the creepo is a teacher, or a teacher who [does not believe in any gods] or [is a religious believer] in a between-subjects manipulation. The results, from around 3400 participants in thirteen countries? People pick the second option if it implies that the serial killer does not believe in God. Put differently, people intuitively assume that the perpetrators of nasty immoral deeds don’t believe in God. Even atheist participants in highly secular countries shared this suspicion. Sarah Schiavone even ran a followup where people intuitively assume that a priest who molests boys for decades is in fact a secret atheist priest!

Country-by-country effects

Within-country (non)effect of individual religious belief

What do people think atheists look like?

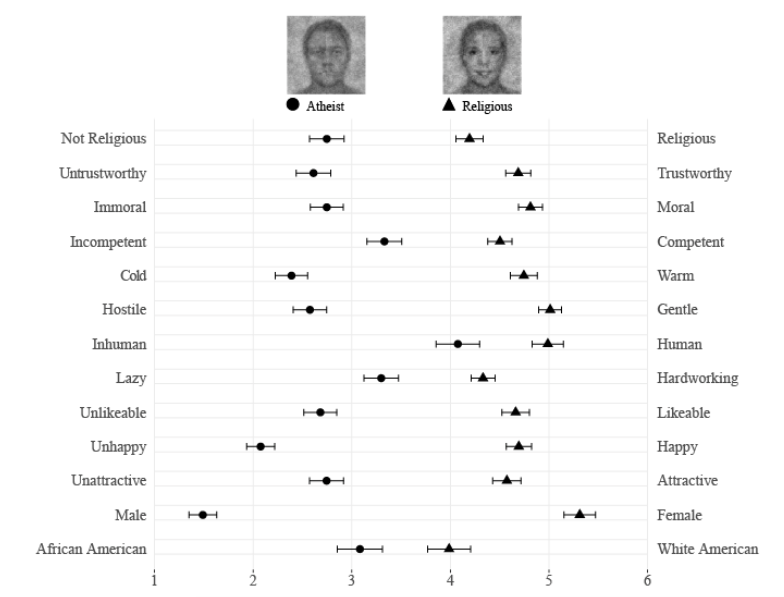

Going beyond intuitive moral suspicion of atheists in researcher-provided scenarios, we can also probe people’s spontaneously generated mental representations of atheists. This project was led by the awesome duo of Jazmin Brown-Iannuzzi (hint: it’s not pronounced ‘jazz-min.’ Try ‘hahs-meen’) and Stephanie McKee. Now in press at JEP: General.

Creating mush-faces

To get at spontaneous representations of atheists, we used a cool technique called reverse correlation (and by ‘we’ I mean ‘they’). Basically you can make a generic blended face and then generate a whole shitload of degraded mush-faces. Then you show participants a shit ton of pairs of these mush-faces and their task is simple: pick the mush-face that looks like it does not (or does, in another condition) believe in God. Then you take all the chosen mush-faces and mash them together into an aggregate mash-mush-face that, voila!, is people’s spontaneously generated mental representation. Here were the results:

aggregate mash-mush-faces for atheists and believers

Not a pretty picture on the left: the atheist face. We then had a separate crop of participants rate these two faces on various attributes. And they thought the atheist face looked like a worthless pile of hot excrement. Finally, we had a third crop of participants read about someone doing immoral or moral actions (kicking a dog, etc). These participants overwhelmingly thought that it was the atheist face doing bad deeds and the theist face doing nice things.

People don't like the scary atheist face very much

So now we return to the opening question:

How many atheists are there?

Well remember the serial killer and the mushface when thinking about whether people will openly admit to atheism over the phone to a stranger. Yeah, maybe people will be a tad reluctant.

In an attempt to get an atheist prevalence estimate less biased by social desirability, we found a task used in criminology and sociology to obtain population prevalence estimates of things without anyone actually having to admit that they are, say, a date rapist or a drug user or an ivory poacher.

It’s called the unmatched count technique. You get a bunch of people and randomly split them into two groups; let’s call them the baseline group and the sensitive group. Both groups get to play a counting game: you give them a list of statements and they tell you how many are true for them (NOT which ones, only the sum). In the baseline group, it’s a list of bland statements (I eat hot dogs regularly; I am wearing a long sleeved shirt; I play the banjo; My favorite color is red). The sensitive group gets the exact same list, with the addition of one sensitive item (I eat hot dogs regularly; I am wearing a long sleeved shirt; I play the banjo; My favorite color is red; I occasionally date rape people). The difference in average scores between these two groups should be attributable to the addition of the sensitive item. If the average scores are 3 and 3.24, respectively, you can infer that around 24% of your sample are date rapists. If they’re 2.8 and 2.9, then you’re dealing with 10% date rapists. Or so the logic goes.

Maxine Najle and I did two versions of this using atheism as the socially sensitive item in two separate nationally representative samples of 2000 people each. And based on this, our best possible guess is that around 26% of Americans don’t believe in God. Much much higher than Gallup’s 11% or Pew’s 3%.

Some other fun facts about this study: the results were messy as hell. Turns out the unmatched count is not all that precise. So it could easily be 20%, it could easily be 35%. That's a pretty wide shrug for 4000 participants. And we even uncovered some findings that made us question whether the damn task even worked. We flag that as our ‘most damning result’ in the paper, and SPPS let us get away with it.

LOL, this was fun to write

There we go, Friendo. Atheists!!! They’re Everywhere!!!***

*** maybe