Cold Open

I just wrapped up what was by far the most fun and fulfilling teaching semester of my career. So, before I explain anything about that title or what’s going to happen in the foreshadowed blog series, I’m going to share the raddest student feedback I’ve ever received. During the last week of my first year Science and Critical Thinking module[1] (that’s more foreshadowing), I used PollEverywhere’s handy Reddit-style upvote/downvote feature to ask students what were the most important skills or concepts they learned. Here are the winners:

Confirmation Bias

System 1/System 2 thinking

Bullshit (a la Frankfurt)

Using THAMES method to evaluate science (more foreshadowing)

Not to trust AI outputs

Critical Thinking

My main goal for this module was to give students a basic toolkit for epistemic self-defense in a world awash in misinformation, poor thinking, and pseudoscientific bullshit. I wanted to help prepare my students to face down that mess, and say “not today, you dork ass losers.”

That student feedback? Exactly the middle fingers I hoped they’d raise, in the face of the bullshit that’s threatening to drown us all.

These incredible students didn’t just pick up critical thinking in my lectures. Oh no, it was far cooler than that. You see, my little Science and Critical Thinking module was just one component in our brand spanking new,

fully bespoke, deluxe-edition 9-module methods, stats, and skills curriculum.

This curriculum is the culmination of a shit ton of work by Brunel Psychology’s methods/stats/skills teaching team: that’s Abbey Page, Mícheál da Barra, James Winters, Caro Di Bernardi Luft, Elena Makovac, and Me (Will).

This blog series is about that exciting new curriculum – the process of designing it, some of the cool innovations we tried, and reflections as it rolls out over the next year. So, welcome to Episode 1 of Don’t Send A Magician To Do A Scientist’s Job, a blog series about our experiments in teaching science to young scientists.

This post is gonna basically brag about some of the cool stuff we’ve done and plan to do, and sketch out the overall curriculum we’ve designed and how we got there. Future posts will delve into individual components, lectures, assessments, wins, fat Ls, and the friends we made along the way. I hope y’all find it entertaining/useful/cautionary/etc and enjoy the ride!

Time for Change

This past summer, Brunel Psychology made Dr. Caro Di Bernardi Luft its inaugural Head of Department (prior to this year, we’d been a Division rather than a Department, which was a distinction). If you’ve been following news about higher ed in the UK, it probably wouldn’t surprise you to learn that she inherited a post-redundancy mess of short staffing and low morale and we needed to recharge our teaching on several fronts to better meet our students’ needs – a monumental task that I’m glad wasn’t mine. But Caro’s really excelled in matching people to roles that fit their expertise and interests in a way that feeds back to the students.

Of relevance to this blog: it was time to revamp our whole methodology and statistics curriculum. These topics are teaching challenges everywhere – students can often approach them with apprehension, and teaching these topics well and engagingly doesn’t always come easily. But there seemed to be room for growth and improvement and cohesion, based on student feedback.

So over the summer, I had the fun privilege of working with Mícheál and Caro and Abbey and James to try to rethink our methodology curriculum from first principles. We approached our task as straightforward, if not easy. We wanted to prepare our students to think critically – about science, about psychology, about the world – while engaging them openly and honestly about the ways that data can flummox our intuitions, the ways that science only aspires towards objectivity, but falls short for inevitably human reasons. Oh and since these modules also hit the students right at the beginning of their university journey, the modules also had to have good vibes, be inspiring, and all that important stuff. No biggie.

On a personal note, the pivot (back) to helping with methods teaching came at a very welcome time. My teaching specialty and passion has always been in methodology, going all the way back to grad school when Dr. Catherine Rawn first mentored me in teaching on UBC’s undergraduate methodology classes. While at Kentucky, I’d specialized in methodology teaching for 6-7 years, across levels and with good success. During those years, I even developed lines of research on methodology. However, since being at Brunel, opportunities to teach methods or statistics had not been forthcoming. The modules were understandably filled when I began; then I was told there was no such thing as a specialist in these domains; then I heard that students inevitably hated stats and methods, so why sink the time in to prepping anything outside the box? One guy told me that HECK one time they’d had a stats or methods instructor with stage magic skills doing sleight of hand, and even THAT couldn’t get the students to like stats or methods.

Hence the genesis of this blog series’ title:

Don’t Send a Magician to Do a Scientist’s Job

The fatalism implied by the plaintive “of course students will always hate stats and methods”, given my years of experience teaching methods well, smacked of bullshit; defeatist bullshit. OF COURSE we could engage and challenge our students, meeting them where they are and showing them the frustrations and challenges and imperfections – but above all the wonder and the utility and the logic of science. Because science is fucking cool, and if you believe that while you’re teaching it, the students appreciate that, no matter their intuitive apprehensions about statistical calculations. Science doesn’t take razzle dazzle or legerdemain; it takes hard work, and creativity, and a stubborn refusal to buy your own bullshit.

So, given a fairly blank slate to work with, what could we come up with? If we could design a whole curriculum to thusly give students the skills to think scientifically – with statistical literacy and intellectual humility and a critical mind – what would that curriculum look like? And how close to that ideal could we get, given our practical constraints?

The Constraints

If you’re familiar with UK higher ed, you’ll realize that change can be slow. Structural changes to teaching – which modules align with which, what assessments look like, things of that nature – take about a year to pass intestinally through successive bureaucratic steps.

So, starting back in about May, we needed to design a curriculum that would be operational for students’ return in September. We could not make any structural changes to modules large enough to affect, say, programme specs.

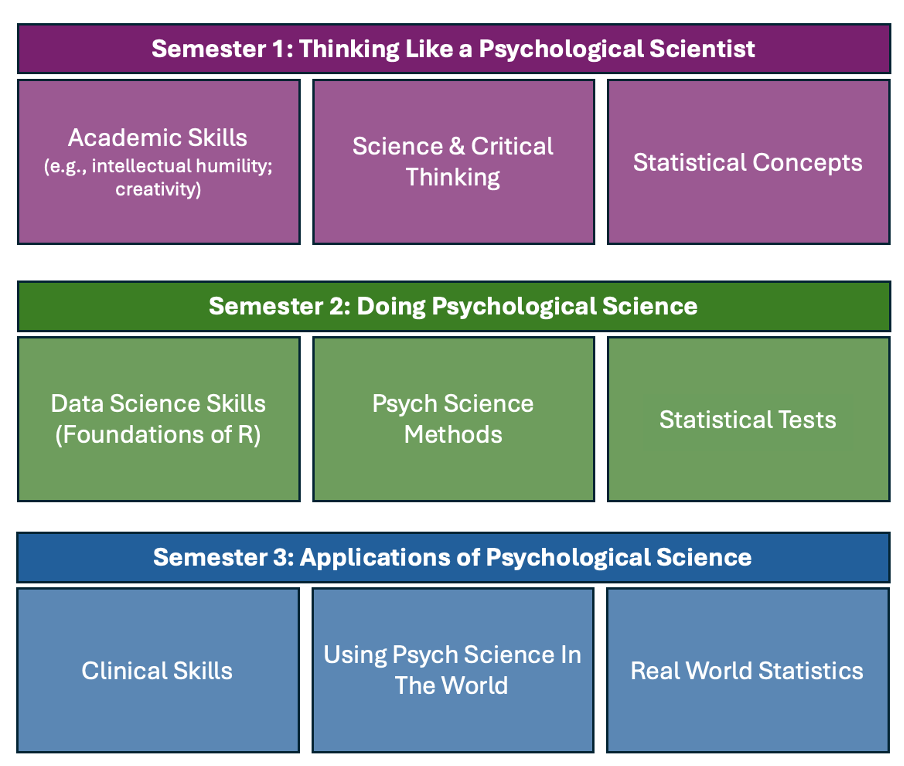

Our overall curriculum was coming off a period of credit realignment and restructuring that ended up grouping some modules together in teams – social psychology pairs with personality psychology, for example. The upshot of this is that our core methodology curriculum now consisted of essentially 9 modules, taught 3 at a time over 3 semesters. Each semester consisted of: one statistics module, one methodology module, and one “skills” module. That was the general framework we had to work within.

We sat down at this point and basically tried to brainstorm how we could best use these 9 modules. And what an incredible luxury it was! We had 9 full modules to fill, covering half of our students’ semesters at university. We didn’t have to cram all the methods teaching into one module and all the stats teaching into another (as I had as an undergraduate), or even split it across a small handful. We could really take our time and let our students develop their learning in a cohesive way across the blocks.

If we did it right, the students should be able to feel horizontal cohesion across all three modules that they would be taking simultaneously in any semester, and vertical continuity across semesters. Things could fit together while they also progressed. We also wanted to pre-empt common friction points that occur when humans are forced to learn eldritch arcana like frequentism, and really let some key ideas marinate.

More broadly, we wanted to design a curriculum that would equip our students to be successful – as students, and in life. We wanted to design a curriculum that could help the students leverage their own learning in other modules, simply because they’ve learned how to approach information critically, and how to approach their own learning with intellectual humility. We could design a scientific curriculum that we would’ve loved to have taken as students!

These three blocks of modules span every psychology student’s first, second, and third semesters on campus. They’re the bridge from students fresh off A-levels and arriving on campus to students starting to think about placements and dissertations. The skills built in modules like this also flow outward to the rest of the curriculum – better scientific thinking makes it easier to teach people scientific topics, go figure.

So that was the goal. Many hours and some very full marker boards later, here’s what we came up with:

The Overall Layout

We decided to have a core organizing theme for each semester, a narrative to which students could orient their learning journey.

Autumn of first year – most folks’ first semester as a university student – was devoted to Thinking Like a Psychological Scientist, it was meant to be broad and big-picture. Moving from autumn to spring, the purview narrows and deepens, focusing on Doing Psychological Science. To kick off everyone’s second year, the third semester of our progression gets real and it gets messy, focusing on the exciting complications that result when we grapple with Applications of Psychological Science.

Each of these thematic blocks is composed of one statistics module, one methodology module, and one “skills” module of one sort or another – all suited to the corresponding block theme. Here’s the full layout, I’ll unpack some details of each after.

Thar she blows, our white whale!!! It’s the blueprint for what we’re trying to build, a description of the rooms we’d like to have inside. Presumably several other tenuous and mixed metaphors to boot. To unpack:

Semester 1: Thinking Like a Psychological Scientist

Academic Skills.

Students start out with Caro in Academic Skills. The goal here is using what we know from cognitive science to help students build skills that will help them as students – Caro’s guiding themes were intellectual humility and creativity. This module sets our students up to student to the best of their capabilities. In Caro’s words:

Science and Critical Thinking.

My main baby this year! In lieu of diving right into some of the perhaps more expected introductory methods training, we opted to open with a general science and critical thinking module as the methods component. I was lucky enough to get to teach this one.

I tried to make it a sort of chaotic-good cognitive-and-cultural-science-focused version of like a Calling Bullshit setup: thinking about how we think (for better or worse), how we can think more clearly, and how science acts as a mental prosthesis to help us think better. The goal was as much to encourage a way of thinking as it was to teach any specific facts or concepts.

I’ll have so many more details about this one in subsequent blog posts, but it had some fun bells and whistles along the way – a replication study of a Psych Science classic, advice on critical thinking from eminent guests, confounding gifs and memecraft. The technical term for the broad-spectrum approach I aspired towards is: “whole-assed.”

Statistical Concepts.

Okay, now things are gonna start getting cool. Look at the roadmap above. We’ve got something called Statistical Concepts, something called Statistical Tests, and then we’ve got a Data Science module. Then in the second year there’s Real World Statistics. The basic idea here goes something like this:

Learning statistics is hard in at least 4 different ways.

First, you’ve gotta learn a new set of concepts with their own often counterintuitive logic; people need to understand the conceptual guts that underlie all of our tests. What do numbers like t or F or p or d even mean?

Second, there’s calculation – the meat of traditional statistical curricula. Hereabouts lie your tests t, F, and chi-square; your OVAs AN and MAN. Sampling distributions, standard errors, whatnot. How do we calculate the numbers (like t or p)?

Third, there’s computation: how do you handle data and make the computer spit out the right numbers?

Fourth, application: how do we ask complex questions and analyze real data, warts and all?

We’ve split these four challenges into four modules, letting students focus separately on theory, calculation, computation, and messy application.

To kick things off during autumn of first semester, Mícheál and I co-teach our Statistical Concepts module – theory. The general idea was to try to develop people’s intuitions about sampling and estimation and null hypothesis testing in a gentle, largely pictorial, conceptual way. Minimal calculations – think calculating a Mean or Standard Deviation in Excel, no more. But we limber people up for the full conceptual gymnastics of null hypothesis testing. Only then do they proceed to the second semester where these newfangled statistical intuitions are put to use.

Which brings us to…

(note: our first full cohort of students has just arrived here)

Semester 2: Thinking Like A Psychological Scientist

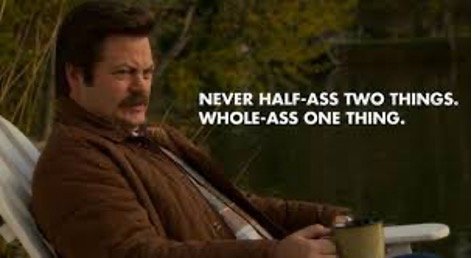

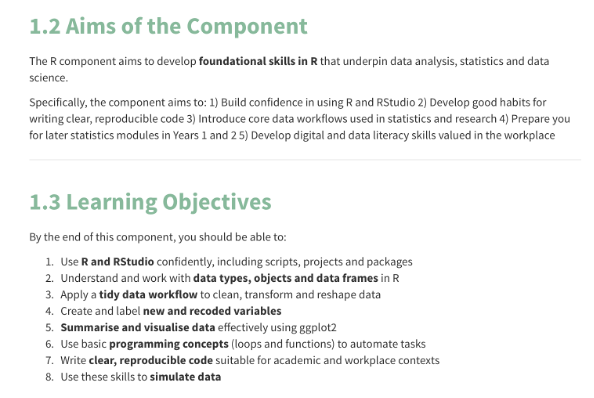

Foundations of R For Statistics and Data Science.

The Skills component of second semester is the one where Abbey Page and James Winters teach all our students how to use R. No biggie. They’re developing an in-house custom text for that, by the by.

Research Methods in Psychological Science.

Mícheál De Barra has long been leading our very strong core psych methods module and continues to do so. This is the module where students really dive into the details of methodology – what do psychology studies look like? What do good studies tend to do? This methods module is our clean pivot from all the big picture ranting and hand-waving that I got to do first semester, to the harder work of actually doing the research. To that end, students each conduct what Mícheál’s been calling the “N-of-1” study: each student designs a repeated measures experiment, with themselves as participant, analyst, and researcher.

Statistical Tests.

Mícheál and I, if we’ve done our jobs, have left the students with a nice conceptual understanding of what statistics tries to do. But we really haven’t shown them how to do much of anything. They might know that a t-test is considering magnitude of between-group differences, relative to within-group spread….but they’ve yet to do a t-test. Or any other test, save their first semester multiple choice exam.

James Winters gets to pick up that mess and show our students how to actually apply the concepts they’ve learned to different data analytic problems. Basically a voyage from chi-square to the general linear model. Sleeves up, learning statistics by doing statistics, in a hybrid lecture/lab format with students on computers the whole time.

Semester 3: Applications of Psychological Science

Clinical Skills.

Much of our Methods/Stats/Skills curriculum is aimed at research, but research skills aren’t the only skills that matter to psychological scientists. In the third semester, Elena Makovac teaches our students about clinical applications and skills.

Using Psychological Science in the World.

Students started this progression with my nonsense. They’ll probably get to end with my nonsense. To wrap the methods trajectory, I’ll be leading a very-much-still-in-development module that I’m hoping will be sort of an outward-facing mirror image of my first year Science and Critical Thinking module. Instead of reflecting on our thinking and how science can help us do it better as individuals, we’ll turn what we’ve learned about science and cognition outward, and tackle topics like misinformation spread, conspiracy theories, spread of poorly evidenced health information, and the like. Along the way I’d like to highlight the methods used by our own researchers, to show our students that psychological science is being actively constructed as we speak. They’ll get to see how that happens here at Brunel, and also how the insights we gain as psychological scientists can inform stuff that’s going on outside the Ivory Tower.

But also…and I cannot stress this enough…this won’t be taught until September and the details sound like a problem for Summer Will. I’m sure he won’t mind.

Real World Statistics.

Find out what happens, when data stop being polite, and start getting real… Real World Statistics!, with Abbey Page

Abbey takes students beyond analyses whose assumptions check out. They’ll do all sorts of cool stuff: play with DAGs, learn about confounders, think about missingness. And that would be the capstone on 4 complete modules on statistics, that gradually (and often separately!) work through 1) the conceptual underpinnings of frequentism and null hypothesis significance testing, 2) the model families and tests that let us ask different questions, 3) the software and programming skills to ask these questions and deal with data generally, and 4) what life as an applied data analyst actually looks like.

You (well, they/us) Are Here

And that’s the whole layout!

Our first cohort of students have just finished their first semester (well, I guess technically some pesky assessments are currently underway).

I’ll shoot for a blog post or so a week now, running through our experiences putting this together. I’ll try to shame my colleagues into contributing at some point, or perhaps I’ll try a classic Tom Sawyer Fence Ruse to get them involved. Either way, you’ll hear from more than just me. Probably maybe. Depends on if they realize just how fun it can be to write a blog post.

And to whet appetites, here are some blog topics I’m thinking of doing:

An overview of my Science & Critical Thinking module, because it was so much fun

How we went about trying to lay a conceptual groundwork for thinking about statistics, without much by way of calculation or computation

Caro’s blend of creativity and intellectual humility as grounding principles

The time ChatGPT advised me to drink bleach to get smarter, because 200+ of Richard Lynn’s publications are in the training data and it equates lighter skin (e.g., bleach) with intelligence

The Gang Figures Out Assessments

Our Replication Study! The assessment for 2 of the methods modules involved writing up the results of a large replication study that we ran on Prolific. Would a 1800+ cite Psych Science hold up?

Elena’s Clinical Highlights (would be sooooooooo fun to write, just like all blog posts)

The THAMES method for reading science

Skiing With Dynamite: My mid-semester “wow have I fucked everything up beyond repair?” week

James and Abbey Are Gonna Have So Much Fun Blogging About Teaching R, Because Blogging Is Fun

4 Questions. I asked a handful of experts the same 4 questions, and their answers were fascinating:

1. What’s the big question that motivates your work?

2. What makes science work well?

3. How can students use AI and developing tech safely and responsibly?

4. What’s one tip for critical thinking?

Assorted Shenanigans: Activities that enlightened or did the opposite

We had an amazing time putting this together and are in the midst of busting our asses to make it work in practice. I hope you find something funny or useful reading along.

Be kind to each other, y’all!

PS…

[1] “Module” at Brunel is roughly equivalent to “class” in US higher ed parlance. PSYCH101 would be a class lots of places, it’s a module here. Capiche?